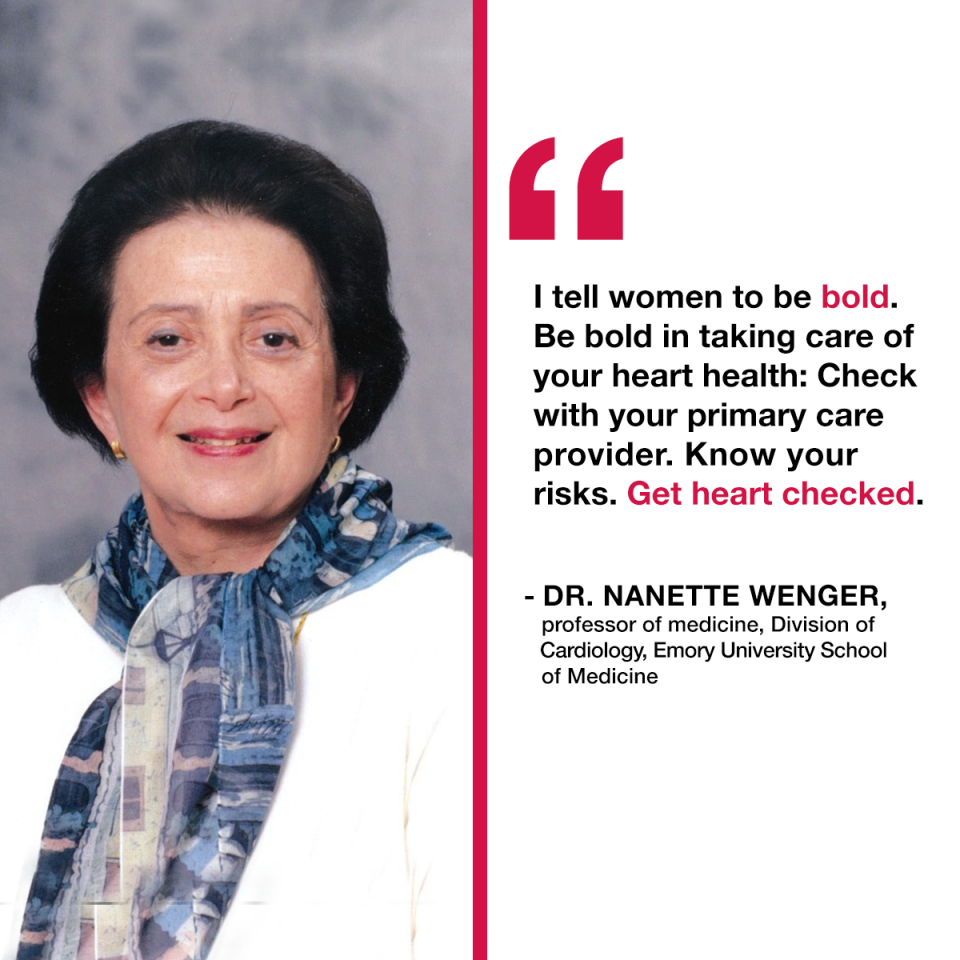

We recently asked a pioneer and champion for women’s heart health—Dr. Nanette Wenger, professor of medicine, Division of Cardiology, Emory University School of Medicine and founding consultant, Emory Women’s Heart Center—to share her thoughts on the history of women’s heart disease. Over her 50+ year career, Dr. Wenger has dedicated her work to research, prevention and treatment of women’s cardiovascular disease.

When I started my career, heart disease was viewed as a man’s problem. Early on, when I saw women patients with heart disease and tried to search for evidence for their diagnoses and management, there was none. My earliest efforts were to contact the various specialty groups, and the earliest success was with the National Heart Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which is now the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

Asking questions was my biggest contribution, and I challenged enough people that they decided to organize a workshop on women’s heart disease. The workshop eventually became a national conference whose deliberations were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. It challenged the supposition that this was a man’s disease and showed that women were very seriously affected by the adverse outcomes of heart disease.

Over the course of my career, the change in how we’re addressing women’s heart disease has been stunning. Until the year 2000, the decline in U.S. cardiovascular mortality was only in men—even though every year since 1984, more women than men died of cardiovascular disease. Beginning in 2000, there was a striking decline in CVD mortality in women. That’s due to the coming together of all the data and its application in clinical practice. In 2013 and 2014, for the first time ever, fewer women than men died of heart disease. We—women—are thrilled to be in second place and hope to stay there.

Is our work finished yet? Nowhere nearly. But at least we’ve made some progress.

The challenge now is not examining women homogenously. Heart disease isn’t just a medical problem: it’s related to social determinants such as education, psycho-social issues, insurance coverage, governmental policies, etc.

For example, much of my population at Grady Memorial Hospital is from marginalized communities. I want them to exercise but they don’t feel safe outside. I advise them to eat healthier foods, but they live in a food desert. They have smokers in their home. They have problems with access to care and insurance. We must solve those problems as well.

Women also have to believe they are vulnerable before they’ll take preventive measures. Many women don’t have the information about their risk. We are also seeing an uptick of smoking behavior in teenage girls right now. And we’re dealing with sedentary lifestyles, obesity, and a number of other risk factors that mean younger women are not experiencing the same declines in mortality now that older women are—in fact, since 2014, mortality in younger women has started to rise.

Most of all, we must get care to women wherever they are. In the medical community, embedding is the secret to doing this successfully. At the Emory Women’s Heart Center, we have cardiologists embedded in the pre-eclampsia clinic with our OB/GYN colleagues (Editor’s note: for more information about pregnancy and heart health, click here.). When new moms come for their six-week check-up, we can check their cardiovascular health, identify cardiomyopathy, etc. We are doing the same with autoimmune disorders and in our cancer centers at the Winship Clinic, where therapies for breast and other cancers can initiate heart problems. We embed our cardiologists throughout women’s care, and encourage other health care providers to do the same.

I tell women to be bold. Be bold in taking care of your heart health: Check with your primary care provider. Know your risks. Get your heart checked.